|

|

|

| Correlation analysis between urinary crystals and upper urinary calculi |

Xi Zhanga,Yang Zhengb,Yichun Wanga,Xiyi Weia,Shuai Wanga,Jie Zhengc,Jixiang Yaoc,Chen Xud,Zhijun Caod,Chao Qina,*( ),Lujiang Yie,*( ),Lujiang Yie,*( ),Ninghong Songa,*( ),Ninghong Songa,*( ) )

|

aDepartment of Urology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China

bNanjing Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Nanjing Hospital of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing, China

cDepartment of Urology, Wuhu Hospital Affiliated to East China Normal University, Wuhu, China

dDepartment of Urology, Suzhou Ninth People's Hospital, Soochow University, Suzhou, China

eDepartment of Laboratory, the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China |

|

|

|

|

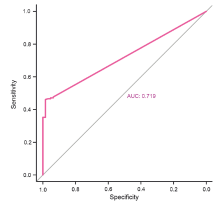

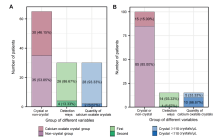

Abstract Objective: This study aimed to analyze the correlation between urinary crystals and urinary calculi. Methods: Clinical data, including urinary crystal types, were collected from 237 patients with urinary calculi. The detection rate of urine crystals and their correlation with stone composition were analyzed. The receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was used to determine the best cut-off value for predicting stone formation risk based on calcium oxalate crystals in urine. Results: Calcium oxalate was the most common component in 237 patients. Among them, 201 (84.81%) patients had stones containing calcium oxalate. In these patients, calcium oxalate crystals were detected in 45.77% (92/201) of cases. In different groups of calcium oxalate stones, calcium oxalate crystals accounted for more than 90% of the total number of crystals detected in each group. The detection rate of calcium oxalate crystals was higher in first-time stone formers than in recurrent patients. The receiver operating characteristic curve analysis suggested a cut-off value of 110 crystals/μL for predicting stone formation, validated with 65 patients and 100 normal people. Conclusion: Calcium oxalate crystals in urine can predict the composition of calcium oxalate stones and indicate a higher risk of stone formation when the number exceeds 110 crystals/μL. This non-invasive method may guide clinical treatment and prevention strategies.

|

|

Received: 19 April 2023

Available online: 20 October 2024

|

|

Corresponding Authors:

*E-mail address: qinchao@njmu.edu.cn (C. Qin), lj.yi@njmu.edu.cn (L. Yi), songninghong_urol@163.com (N. Song).

|

|

|

| Stone composition | Total | Urinary crystal | None urinary crystal | Crystallization detection rate, % | Match, % | Mismatch,% | COC detection rate, % | | COC | PC | UC | CC | | Calcium oxalate calculus | 97 | 42 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 51 | 47.42 | 91.30 | 8.70 | 43.30 | | Calcium oxalate mixed carbonate apatite | 83 | 43 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 39 | 53.01 | 97.73 | 2.27 | 51.81 | | Calcium oxalate mixed uric acid calculus | 20 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 45.00 | 100 | 0 | 35.00 | | Struvite mixed carbonate apatite | 16 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 43.75 | 71.43 | 28.57 | 6.25 | | Uric acid calculus | 15 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 40.00 | 66.67 | 33.33 | 6.67 | | Struvite calculus | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | | Carbonate apatite mixed hydroxyapatite | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | | Calcium oxalate mixed l-cystine calculus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | | Carbonate apatite mixed l-cystine calculus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | | l-cystine calculus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | | Total | 237 | 95 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 123 | 48.10 | 91.23 | 8.77 | 40.08 |

|

|

The crystal detection, match, mismatch, and COC detection rate in various urinary calculi.

|

|

|

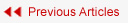

The morphology of urine crystals under the microscope (10×40). (A) The morphology of dihydrated calcium oxalate crystal; (B) The morphology of monohydrated calcium oxalate crystal; (C) Type I morphology of phosphate crystals; (D) Type II morphology of phosphate crystals; (E) Type I morphology of uric acid crystal; (F) Type II morphology of uric acid crystal.

|

| Characteristics | Calcium oxalate mixed carbonate apatite (n=43) | Calcium oxalate mixed uric acid calculus (n=7) | Calcium oxalate calculus (n=42) | p-Value | | Gender, n (%) | | | | 0.659 | | Male | 30 (32.6) | 6 (6.5) | 29 (31.5) | | | Female | 13 (14.1) | 1 (1.1) | 13 (14.1) | | | Age, year, n (%) | | | | 0.040 | | ≤52 | 27 (29.3) | 2 (2.2) | 16 (17.4) | | | >52 | 16 (17.4) | 5 (5.4) | 26 (28.3) | | | Stone location, n (%) | | | | 0.023 | | Kidney and ureter | 12 (13.0) | 0 (0) | 18 (19.6) | | | Ureter | 13 (14.1) | 2 (2.2) | 3 (3.3) | | | Kidney | 18 (19.6) | 5 (5.4) | 21 (22.8) | | | History, n (%) | | | | 0.040 | | First | 30 (32.6) | 2 (2.2) | 32 (34.8) | | | Recrudescence | 13 (14.1) | 5 (5.4) | 10 (10.9) | |

|

|

Differences in the detection of calcium oxalate crystals in various clinical phenotypes (n=92).

|

|

|

Differences in the urine specific gravity and maximum stone diameter between calcium oxalate crystal and non-crystal groups. (A and B) Calcium oxalate stones; (C and D) Calcium oxalate mixed carbonate apatite stones; (E and F) Calcium oxalate mixed uric acid stones. ? p<0.05; ?? p<0.01; ??? p<0.001; NS, no significance.

|

|

|

Screening for the best cut-off for predicting the risk of stone formation through the receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. AUC, area under the curve.

|

|

|

Validation of the best cut-off for predicting the risk of stone formation. (A) The distribution, retest results, and proportion of calcium oxalate crystal and non-crystal groups in the calcium oxalate stone validation group; (B) The distribution, retest results, and proportion of calcium oxalate crystals and non-crystal groups in the normal validation group.

|

| [1] |

Scales CD, Smith AC, Hanley JM, Saigal CS. Prevalence of kidney stones in the United States. Eur Urol 2012; 62:160-5.

doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.03.052

pmid: 22498635

|

| [2] |

Wang W, Fan J, Huang G, Li J, Zhu X, Tian Y, et al. Prevalence of kidney stones in mainland China: a systematic review. Sci Rep 2017; 7:41630. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41630.

doi: 10.1038/srep41630

pmid: 28139722

|

| [3] |

Zeng G, Mai Z, Xia S, Wang Z, Zhang K, Wang L, et al. Prevalence of kidney stones in China: an ultrasonography based cross-sectional study. BJU Int 2017; 120:109-16.

doi: 10.1111/bju.13828

pmid: 28236332

|

| [4] |

Alexander RT, Hemmelgarn BR, Wiebe N, Bello A, Morgan C, Samuel S, et al. Kidney stones and kidney function loss: a cohort study. BMJ 2012; 345:e5287. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e5287.

|

| [5] |

Khan SR, Pearle MS, Robertson WG, Gambaro G, Canales BK, Doizi S, et al. Kidney stones. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2:16008. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.8.

doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.8

pmid: 27188687

|

| [6] |

Singh P, Enders FT, Vaughan LE, Bergstralh EJ, Knoedler JJ, Krambeck AE, et al. Stone composition among first-time symptomatic kidney stone formers in the community. Mayo Clin Proc 2015; 90:1356-65.

doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.07.016

pmid: 26349951

|

| [7] |

Worcester EM, Coe FL. Clinical practice. Calcium kidney stones. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:954-63.

|

| [8] |

Kok DJ, Boellaard W, Ridwan Y, Levchenko VA. Timelines of the “free-particle” and “fixed-particle” models of stoneformation: theoretical and experimental investigations. Urolithiasis 2017; 45:33-41.

doi: 10.1007/s00240-016-0946-x

pmid: 27915394

|

| [9] |

Finlayson B. Physicochemical aspects of urolithiasis. Kidney Int 1978; 13:344-60.

pmid: 351263

|

| [10] |

Frochot V, Daudon M. Clinical value of crystalluria and quantitative morphoconstitutional analysis of urinary calculi. Int J Surg 2016; 36:624-32.

doi: S1743-9191(16)31032-9

pmid: 27847293

|

| [11] |

Robert M, Boularan AM, Delbos O, Guiter J, Descomps B. Study of calcium oxalate crystalluria on renal and vesical urines in stone formers and normal subjects. Urol Int 1998; 60:41-6.

pmid: 9519420

|

| [12] |

Fink HA, Wilt TJ, Eidman KE, Garimella PS, MacDonald R, Rutks IR, et al. Medical management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians clinical guideline. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158:535-43.

doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-7-201304020-00005

pmid: 23546565

|

| [13] |

Brikowski TH, Lotan Y, Pearle MS. Climate-related increase in the prevalence of urolithiasis in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105:9841-6.

|

| [14] |

Ye Z, Zeng G, Yang H, Li J, Tang K, Wang G, et al. The status and characteristics of urinary stone composition in China. BJU Int 2020; 125:801-9.

doi: 10.1111/bju.14765

pmid: 30958622

|

| [15] |

Burns JR, Finlayson B, Gauthier J. Calcium oxalate retention in subjects with crystalluria. Urol Int 1984; 39:36-9.

pmid: 6730116

|

| [16] |

Robertson WG. Potential role of fluctuations in the composition of renal tubular fluid through the nephron in the initiation of Randall’s plugs and calcium oxalate crystalluria in a computer model of renal function. Urolithiasis 2015; 43(Suppl 1): 93-107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-014-0737-1.

|

| [17] |

Khan SR, Hackett RL. Urolithogenesis of mixed foreign body stones. J Urol 1987; 138:1321-8.

doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)43592-0

pmid: 3312647

|

| [18] |

Worcester EM. Urinary calcium oxalate crystal growth inhibitors. J Am Soc Nephrol 1994; 5:S46-53. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.V55s46.

doi: 10.1681/ASN.V55s46

pmid: 7873744

|

| [19] |

Lieske JC, Leonard R, Toback FG. Adhesion of calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals to renal epithelial cells is inhibited by specific anions. Am J Physiol 1995; 268:F604-12. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.1995.268.4.F604.

|

| [20] |

Gill WB, Jones KW, Ruggiero KJ. Protective effects of heparin and other sulfated glycosaminoglycans on crystal adhesion to injured urothelium. J Urol 1982; 127:152-4.

doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)53650-2

pmid: 6173491

|

| [21] |

Cavanaugh C, Perazella MA. Urine sediment examination in the diagnosis and management of kidney disease: core curriculum 2019. Am J Kidney Dis 2019; 73:258-72.

doi: S0272-6386(18)30873-4

pmid: 30249419

|

| [22] |

Berg W, Schnapp JD, Schneider HJ, Hesse A, Hienzsch E. Crystaloptical and spectroscopical findings with calcium oxalate crystals in the urine sediment: a contribution to the genesis of oxalate stones. Eur Urol 1976; 2:92-7.

pmid: 971679

|

| [23] |

Azoury R, Garside J, Robertson WG. Calcium oxalate precipitation in a flow system: an attempt to simulate the early stages of stone formation in the renal tubules. J Urol 1986; 136:150-3.

doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)44761-6

pmid: 3712603

|

| [24] |

Robertson WG, Peacock M, Nordin BE. Calcium crystalluria in recurrent renal-stone formers. Lancet 1969; 2:21-4.

doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)92598-7

pmid: 4182793

|

| [25] |

Daudon M, Hennequin C, Boujelben G, Lacour B, Jungers P. Serial crystalluria determination and the risk of recurrence in calcium stone formers. Kidney Int 2005; 67:1934-43.

pmid: 15840041

|

| [1] |

Siddalingeshwar Neeli. Effect of tamsulosin versus tamsulosin plus tadalafil on renal calculus clearance after shock wave lithotripsy: An open-labelled, randomised, prospective study[J]. Asian Journal of Urology, 2021, 8(4): 430-435. |

| [2] |

Masahiro Matsuki,Atsushi Wanifuchi,Ryuta Inoue,Fumiyasu Takei,Yasuharu Kunishima. Ureteral calculi secondary to a gradually migrated acupuncture needle[J]. Asian Journal of Urology, 2021, 8(1): 134-136. |

| [3] |

Siddharth Pandey,Tanica Pandey,Apul Goel,Ajay Aggarwal,Deepanshu Sharma,Tushar Pandey,Satya sankhwar,Gaurav Garg. Utility of trans-vaginal ultrasound in diagnosis and follow-up of non-pregnant sexually active females with lower ureteric calculi[J]. Asian Journal of Urology, 2020, 7(1): 45-50. |

| [4] |

Guangju Ge,Zhenghui Wang,Mingchao Wang,Gonghui Li,Zuhao Xu,Yukun Wang,Shawpong Wan. Inadvertent insertion of nephrostomy tube into the renal vein following percutaneous nephrolithotomy: A case report and literature review[J]. Asian Journal of Urology, 2020, 7(1): 64-67. |

| [5] |

Rajeev Thekumpadam Puthenveetil, Debajit Baishya, Sasanka Barua, Debanga Sarma. Unusual case of nephrocutaneous fi stula -Our experience[J]. Asian Journal of Urology, 2016, 3(1): 56-58. |

|

|

|

|